A guest post by Mary A. Wood

A guest post by Mary A. Wood

“The essential function of art is moral. Not aesthetic, not decorative, not pastime and recreation. . . . But a passionate, implicit morality, not didactic. A morality which changes the blood, rather than the mind. Changes the blood first. The mind follows later, in the wake.” —D.H. Lawrence

“Alchemy starts in desire; desire needs direction.” —James Hillman

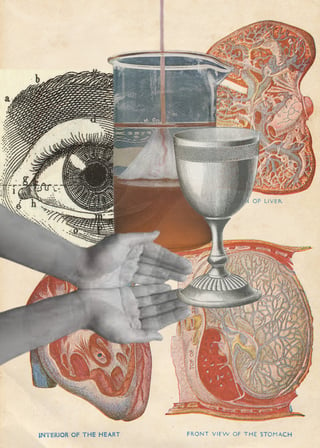

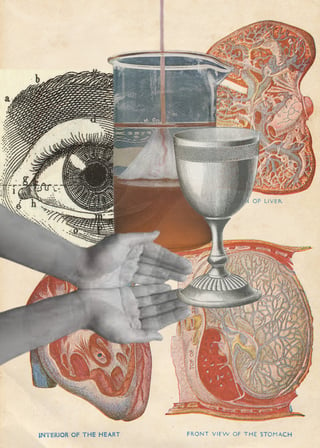

Blood is thicker than water—or so the saying goes. Like a myth in miniature, a complete worldview is illuminated in just five words. The bond of family or tribe, whether formed through birth, marriage or intense shared experiences (such as military service) is evident as well when we speak of “blood brothers,” “bloodlines,” and “blood oaths.” Blood itself has always been highly symbolic. It “evokes life’s precious value” as it courses through veins, yet when it escapes it “congeals into a dark haunting symbol of death” (Ronnberg 396). Those that work with blood, such as the surgeon and nurse, share a specialized sphere with the priest who daily transforms water and wine into imaginal blood. Through a multitude of ritualized signals and ceremony (such as uniforms, insignia, and dedicated locations where their work is conducted) all continue to be set apart from the rest of society much like the ancient shaman, alchemist and healer. As “workers of blood” these modern-day practitioners fulfill vital and even sacred roles, yet they are not alone—the artist and the poet are also inheritors of the talents, and the duties, of those who work with blood—“the poet is the transcendental doctor” (Novalis, qtd. in Hillman, Alchemical 340). When the bonds of blood begin to boil over and congeal into unconscious, ominous masses, it is not the physician, nor even the politician, but the artist and poet that can best halt the contagion.

Read More

A guest post by Mary A. Wood

A guest post by Mary A. Wood