A guest post by Mary A. Wood

A guest post by Mary A. Wood

“The essential function of art is moral. Not aesthetic, not decorative, not pastime and recreation. . . . But a passionate, implicit morality, not didactic. A morality which changes the blood, rather than the mind. Changes the blood first. The mind follows later, in the wake.” —D.H. Lawrence

“Alchemy starts in desire; desire needs direction.” —James Hillman

Blood is thicker than water—or so the saying goes. Like a myth in miniature, a complete worldview is illuminated in just five words. The bond of family or tribe, whether formed through birth, marriage or intense shared experiences (such as military service) is evident as well when we speak of “blood brothers,” “bloodlines,” and “blood oaths.” Blood itself has always been highly symbolic. It “evokes life’s precious value” as it courses through veins, yet when it escapes it “congeals into a dark haunting symbol of death” (Ronnberg 396). Those that work with blood, such as the surgeon and nurse, share a specialized sphere with the priest who daily transforms water and wine into imaginal blood. Through a multitude of ritualized signals and ceremony (such as uniforms, insignia, and dedicated locations where their work is conducted) all continue to be set apart from the rest of society much like the ancient shaman, alchemist and healer. As “workers of blood” these modern-day practitioners fulfill vital and even sacred roles, yet they are not alone—the artist and the poet are also inheritors of the talents, and the duties, of those who work with blood—“the poet is the transcendental doctor” (Novalis, qtd. in Hillman, Alchemical 340). When the bonds of blood begin to boil over and congeal into unconscious, ominous masses, it is not the physician, nor even the politician, but the artist and poet that can best halt the contagion.

Beyond Reason—Bonds of Body and Soul

As an artist, mythologist, educator and artist’s mentor, I am inspired to approach situations from depth psychological and archetypal points of view—to “see-through” whatever presents itself on the surface. Simply stated, these perspectives (associated with C.G. Jung and James Hillman respectively) advance the notion that human beings are directed in large measure by the unconscious forces of psyche or soul, and that it is beneficial to come into some type of “right relationship” with these forces. These perspectives are not so different from many spiritual teachings. In addition, they have affinities with cutting-edge neuroscientific theories, which hold that human beings are largely directed by autonomous actions occurring within the brain and the “greater nervous system” (Eagleman 219). Neuroscientists have much in common with depth psychologists when they argue: “Although our decisions may seem like free choices, no good evidence exists that they actually are” (Eagleman 162), and that even as “conscious observers” of our experience, we are “not the deep cause of it” (Harris 44). These are humbling, even startling statements, to say the least.

Whether influenced by a bodily organ, which we can locate, or by an entity/substance known as psyche/soul, which we cannot locate, human beings are left in the same situation: we act in partnership with something that is “other.” Artists, poets and creators have long expressed that this is indeed the case. Those who create have always wrestled with the dynamics of free will and unconscious motivations alongside the philosopher, theologian and psychologist.

Blood Bonds and Mythic Unbinding

Like many others, I watched the 2016 US Presidential campaign unfold with an increasing sense of concern, even dread. I urged my conservative friends and family to consider the impact of a Donald Trump administration on the most vulnerable in our society. I felt cautiously optimistic that they would extend their empathy beyond their immediate families, political party or particular religion. Yet late on the evening of Election Day, I found myself asking, “What did I miss?” “How could the polls have been so wrong?” “Who will suffer first?”

Both the 2016 US Presidential election and the so-called “Brexit” vote in the United Kingdom will continue to be analyzed and re-analyzed for years to come. Regardless of ideological outlook, many commentators point to a backlash of the “white working-class,” a group whose lives have increasingly become more difficult due to advances in technology, globalization, and income inequality, among other intertwined factors. In addition (and regardless of available data that suggests otherwise) a significant number of individuals in both the UK and the US have expressed resentment for what they sense is an overwhelming tide of migrants entering their countries—strangers bringing unwelcome customs and utilizing scarce services while contributing little in return (Travis).

In the US, many citizens have expressed feelings of estrangement in their own country. The advancement of legislation over many years related to civil liberties, voting rights, abortion access and gay marriage, along with the increasing diversity of the nation’s population have led some to feel as though the American way of life (as they define it) is under attack (Harper).

The deluge of election analysis appears to reveal not so much a rational and reasoned disagreement on policies; i.e., small government vs. large, public management vs. privatization, protectionism vs. fluid international trade, nor solely the eruption of rage simmering within a neglected white underclass. Many well-off individuals, “moderate” voters and a healthy percentage of minority citizens chose to cast their votes for the Republican nominee regardless of the cascade of incidents and comments that would have ended the political aspirations of a traditional candidate. Strikingly, even citizens with minority and LGBT members of their own family (their blood) voted for Donald Trump regardless of evidence of the harm that could befall their very own family members (Swanson). Clearly there is something more at work here than reasoned decision-making. What we are presented with is something beyond reason, something visceral—attitudes that are passionately felt, as if emanating “from the viscera,” those blood pumping and blood circulating organs of the human body itself (Merriam-Webster). We have come face to face with the power of myth.

A Leap into Myth

Considering the recent election alongside factors that can seduce individuals and countries into authoritarianism, Samadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, argues that Trump did indeed offer his supporters something visceral. He offered them “a sense of meaning, a sense of belonging, that their lives are exciting, that there was something to fight for again—and that is a very natural human impulse.” With this statement, Hamid enters archetypal and mythic territory. The desire for participation in something “extraordinary,” combined with the thrill of potential conquest (winning) found in election battles are very much like those found in sports, religious experience and in warfare. Desire for intensified experience is a human trait, and it will always seek release: “In circumstances where nothing seems important, where nothing—ritual or art—shapes their timeless flow, these strong emotions will nevertheless be stimulated by or attach themselves to excess or extravagance or the extraordinary in whatever guises these assume” (Dissanayake 139-40).

Most of us can recall the stunning photos of President Obama and President Elect Trump together during their first meeting in the Oval Office days after the election. For writer Vinson Cunningham, the facial expressions of the two men are a metaphor for a divided country, a metaphor for what he called “two spiritual Americas”: “They tilt their heads toward different horizons; the nations they see, and describe, overlap seldom, if at all” (Cunningham). When Cunningham uses the words “metaphor” and “spiritual,” he too enters mythic territory. Beyond simply offering a “rational” commentary on current events, he moves us closer to the underlying forces at play (and at war) in American life today—archetypal forces that animate the world of myth. As James Hillman stresses, “rational science . . . can only go so far, only to the edge of understanding. At that point, a leap of imagination is called for, a leap into myth” (Terrible Love 9).

But why myth? For Jung, myth provides something essential for human life— myth provides meaning: “Meaninglessness inhibits fullness of life and is therefore equivalent to illness. Meaning makes a great many things endurable—perhaps everything. No science will ever replace myth, and a myth cannot be made out of any science” (MDR 340).

While myths act as powerful guides, we are generally not aware of their presence or power. The poet Owen Barfield goes so far to suggest that “‘it was not man who made the myths, but myths or the archetypal substance they reveal, which made man’” (Avens 26). Even with a genuine sense of curiosity for our own set of myths, stories and narratives, our conscious minds can be blinded to the forces that move us—we may even come to prefer this blindness (Hillman, Terrible Love 215).

As individuals passionately rally around a dynamic leader and what feels like a vital quest, they can become blinded to the consequences of their actions—actions that would seem abhorrent or amoral in “normal” situations (Berenstein). As C.G. Jung warns: “The most dangerous things in the world are immense accumulations of human beings who are manipulated by only a few heads” (Soul 133). The actions spurred by desire for relief, attachment and meaning can escalate from individual acts of aggression to communal acts such as vigilante mob violence and even war. As James Hillman states: “War begs for meaning, and amazingly also gives meaning, a meaning found in the midst of its chaos. Men who survive battle come back and say it was the most meaningful time of their lives” (Hillman, Terrible Love 10). It would be easy to assume that there is little that can be done to alter the progression of events that seem beyond our control, no matter their potential for destruction. Yet the practitioners of “mythopoeisis,” such as the artist, poet, dancer, novelist, singer, and actor, would be among the first to disagree. They are our contemporary mythmakers, spinning new tales for our time out of humanity’s most essential and enduring themes.

Much as a surgeon sutures torn tissue together, taking care to reconnect all of the severed veins and nerves, the artist is able to do the same with her own set of mythopoetic skills. The “suture” of the surgeon and the “stitching together by story” of the artist are linked; both share their etymological roots in the Sanskrit sutra, the thread that binds into a unified story (Merriam-Webster). As novelist and Nobel Laureate, Toni Morrison observes regarding her vocation as a writer: “words suture . . . the places where blood might flow.”

Alchemy and Activism

Alchemy and Activism

“The essential function of art is moral,” writes D.H. Lawrence in an essay devoted to Walt Whitman. “A morality which changes the blood, rather than the mind. Changes the blood first. The mind follows later, in the wake” (Lawrence 155). Moving blood before mind—a path toward activism begins to reveal itself as Lawrence reminds us that deep, visceral change can be sparked most successfully through interaction with an artwork or participation in art making, rather than through intellectual discourse.

Much of the recent political rhetoric during the past few years has dealt with the fact that we, as Americans, don’t make things anymore, and that many of the fine things that we have made in the past (buildings, bridges, etc.) have been neglected and are in need of rebuilding—it is as if we have been bloated with “thinking,” and starved for “making.” This lament applies equally to the arts. As they continue to recede as an essential part of our communal experience, opportunities to “move the blood” decrease in equal measure. As cultural critic and art historian Camilla Paglia insists:

American culture has become unbalanced by its obsession with the blood sport of politics, a voracious vortex consuming everything in its path. . . . Art is not a luxury for any advanced civilization; it is a necessity . . . . Art unites the spiritual and material realms. In an age of alluring, magical machines, a society that forgets art risks losing its soul. (xviii)

The risks are all too clear and many creators are now hearing the call to intensify, and/or diversify their practices—to step into the imaginal role of the alchemist, one that activates and unites spirit and matter—one who can move blood.

Jungian analyst, Nathan Schwartz-Salant offers a convincing argument for reintroducing alchemical thought when he suggests: “alchemical thinking holds out a way to return to wholeness without abandoning separation and distinctness of process.” The historic alchemists knew “from their own and from accumulated experience of centuries of traditional cultures, that their personalities could be transformed. . . . Their imagination could become a guide to truth” (4-5).

Alchemical operations, both old and new, involve work in secretive, private worlds, much like what occurs within the artist’s studio. However, what is crucial for our time is that practitioners return to their communities in order to share and continue the transformative work. Anaïs Nin demonstrates how our private hermetic endeavors strengthen us for essential public action:

Even in the darkest periods of social history, outer events would be changed if we had a center. It is only in the private world that we can learn to alchemize the ugly, the terrible, the horrors of war, the evils and cruelties of man, into a new kind of human being. I do not say turn away or escape. . . . It is necessary to maintain our responsibilities to society, but we need to create a center of strength and resistance to disappointments and failures in outward events. (60)

Nin’s “alchemizing” points to an oscillation or spiraling between private and public endeavors. Hillman shares this sentiment when he states: “Alchemy starts in desire; desire needs direction” (Alchemical 47). The stories and images generated in the solitude of the studio or at the writing desk must seek out other stories and images already active in the world—as the alchemists believed, “like cures like” (Alchemical 76).

Singing Into Veins and Mythic Rebinding

As we have seen, the emotions that drive the artist to create can be compared with those that compel human beings toward the “extraordinary” experiences of group ceremonies, ritual ecstasy and even violence (Dissanayke 139). Hillman recognizes these parallels and offers a plan of action:

Making invites martial metaphors: slogging through and sticking it out, cutting, breaking, earing, rending, suffering wounds and defeat; uncontrollable rage at obstacles. . . .The verge of madness. The loss of self. . . Aesthetic intensity offers an equivalent of war by providing an obdurate enemy—the image, the material, the ideal—to attack, subdue, convert. Venusian passion also offers the erotics, the sacrifice, a devotion but without doctrine, and a band of comrades dedicated to the same search for the sublime. . . . When both accidental and intentional catastrophes hover over our heads, over the planet itself, we must imagine other ways for civilization to normalize martial fury, give valid place to the autonomous inhuman, and open to the sublime. (Terrible Love 212)

If we take seriously the alchemical premise that “like cures like,” then, as Hillman suggests, the martial impulses that drive both creation and aggression can be “re-spected,” re-imagined and transformed through art and art making, through mythopoesis. Myths can be martialed to cure myths and images can be martialed to cure images.

As a country, we may have indeed forgotten how to make things, but as so many of the neglected amongst us shouted during the election season: “Our desire for making has never died—see us now, because we are dying for lack of making!” Our artists, on the other hand, have never stopped making. As if through some type of magic, the sincere artist (inheritor of the tools of the shaman and alchemist) can somehow sing, paint, write and dance directly into the veins of others—changing the blood that brings the mind along in the wake. These gifts must be nurtured, protected and shared.

While there are as many paths to activism as there are artists, our power is amplified when we create together. Collaboration seems especially critical for this moment since one of the primary modes of control within a despotic government is to “limit or erase the imagination that art provides” (Morrison, “Self-Pity”). Despots recognize the power of authentic artistic expression and we must be vigilant for attempts at dividing and conquering.

Our power may be additionally amplified when artists act as generous hosts. We can invite our friends, neighbors and especially our opponents to “leap into myth” with us by bringing their stories and their desires into the alchemical circle— remember, “desire needs direction.” These will not be attempts at reasoned, logical dialogue and persuasion, but opportunities for initiation and transformation— opportunities for the bonds of blood to be expanded and stitched together with the threads of imagination.

“Passion is never enough, nor skill—but try, for our sake,” urges Toni Morrison. We may even come to say, “How lovely it is, this thing that we have done together” (Nobel lecture). We’ll feel it in our blood.

This article first appeared in the journal Immanence: The Journal of Applied Myth, Legend and Folktale.

Images

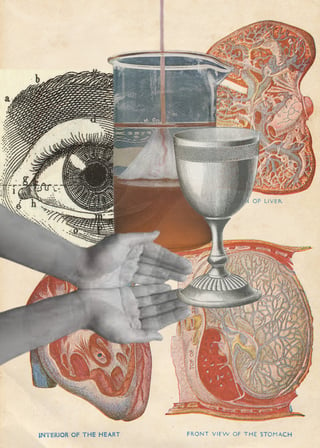

Image: Blood and Change I by Mary A. Wood. Digital collage. 2017

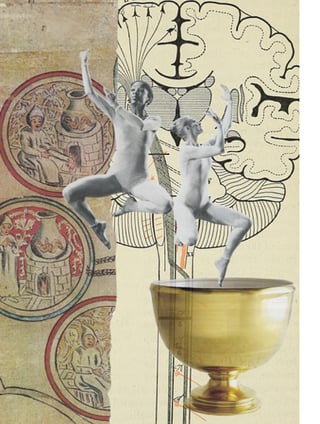

Blood and Change II by Mary A. Wood. Digital collage. 2017

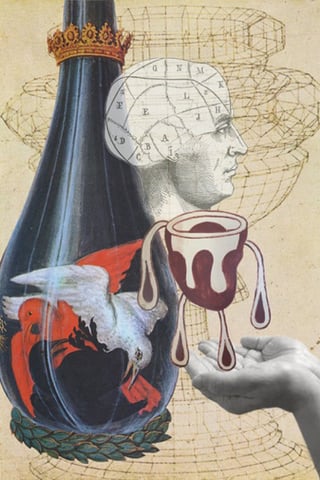

Image: Blood and Change III by Mary A. Wood. Digital collage. 2017

© 2017 Mary A. Wood ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Works Cited

Avens, Roberts. Imagination is Reality: Western Nirvana in Jung, Hillman, Barfield & Cassirer. Spring, 1980.

Berenstein, Erica, et al. “Unfiltered Voices from Donald Trump’s Crowds.” The New York Times, 3 August 2016, nytimes.com

Cunningham, Vinson. “Two Americas in One Photograph.” The New Yorker, 10 November 2016, newyorker.com

Dissanayake, Ellen. What Is Art For? U of W Press, 1988.

Eagleman, David. Incognito: The Secret Life of the Brain. Pantheon, 2011.

Hamid, Shadi. “Why Studying Middle East Politics Helped This Expert Understand Trump’s Appeal.” The Huffington Post, 29 November 2016, huffingtonpost.com

Harper, Jennifer. “Majority of Public: ‘American Way of Life Needs to be Protected Against Foreign Influence.’” The Washington Times, 23 June 2016, washingtontimes.com

Harris, Sam. Free Will. Free Press, 2012.

Hillman, James. Alchemical Psychology. Spring, 2010.

---. A Terrible Love of War. Penguin, 2004.

Jung, C.G. The Earth Has a Soul: C.G. Jung on Nature, Technology, and Modern Life. Edited by Meredith Sabine, North Atlantic Books, 2008.

---. Memories, Dreams, and Reflections. 1963. Edited by Aniela Jaffe, translated by Clara and Richard Winston. Vintage, 1989.

Lawrence, D. H. “Whitman.” Studies in Classic American Literature, edited by Ezra Greenspan and Lindeth Vasey, Vol. 2, Cambridge UP, 2003, 148-61. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. merriam-webster.com

Morrison, Toni. “Nobel Prize Acceptance Lecture.” YouTube, 1993.

---. “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear.” The Nation, 23 March 2015, thenation.com

Nin, Anaïs. “On Truth and Reality.” In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays. Harcourt Brace, 1994, 57-65.

Paglia, Camille. Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt Through Star Wars. Pantheon, 2012.

Ronnberg, Ami and Kathleen Martin. The Book of Symbols. Taschen, 2010.

Schwartz-Salant, Nathan. Jung on Alchemy. Princeton UP, 1995.

Swanson, Carl. “My Parents Voted for Trump and I Didn’t Try To Do Anything About It.” New York Magazine, 11 November 2016, http://nymag.com

Travis, Alan. “Fear of Immigration Drove the Leave Victory—Not Immigration Itself.” The Guardian, 24 June 2016, theguardian.com

Zarin, Cynthia. “A Dance for the Melting Icebergs.” The New Yorker, 25 November 2016, newyorker.com

Mary Antonia Wood, Ph.D. is the owner of Talisman Creative Mentoring, a practice that supports artists and creators of all types. Wood has been as a visual artist for over twenty years, with work featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions and collected by a variety of individuals and institutions. Wood received her doctorate in Mythological Studies from Pacifica Graduate Institute where she is currently adjunct faculty in the Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life Program. In addition to teaching and mentoring fellow artists, Wood is at work on a book for creators of all types based on her doctoral and post-doctoral research on the archetypal forces that shape a creative life. You can visit her webpage at www.talismanmentoring.com and her Instagram gallery at https://www.instagram.com/talisman_creative/

Mary Antonia Wood, Ph.D. is the owner of Talisman Creative Mentoring, a practice that supports artists and creators of all types. Wood has been as a visual artist for over twenty years, with work featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions and collected by a variety of individuals and institutions. Wood received her doctorate in Mythological Studies from Pacifica Graduate Institute where she is currently adjunct faculty in the Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life Program. In addition to teaching and mentoring fellow artists, Wood is at work on a book for creators of all types based on her doctoral and post-doctoral research on the archetypal forces that shape a creative life. You can visit her webpage at www.talismanmentoring.com and her Instagram gallery at https://www.instagram.com/talisman_creative/