A guest blog post by Craig Chalquist, Ph.D., Associate Provost of Pacifica Graduate Institute.

Today is January 9th, which fans of the Great Detective have decided is his birthday. For those into astrology, this would make his natal sun sign studious, hard-working Capricorn. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novels give no indication of the time of day Holmes was born, but I have a feeling, given his interests and how he pursued them, that his natal chart is nocturnal. No doubt Virgo, Mercury, Pluto, and Saturn had a lot to say to each other in it, especially in Houses 12 (secrets, mysteries) and 8 (death, rebirth, other people’s money).

Today is January 9th, which fans of the Great Detective have decided is his birthday. For those into astrology, this would make his natal sun sign studious, hard-working Capricorn. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s novels give no indication of the time of day Holmes was born, but I have a feeling, given his interests and how he pursued them, that his natal chart is nocturnal. No doubt Virgo, Mercury, Pluto, and Saturn had a lot to say to each other in it, especially in Houses 12 (secrets, mysteries) and 8 (death, rebirth, other people’s money).

I encountered Holmes as a result of committing a crime. When I was in high school, a bully made the mistake of picking on my friends and me. The school authorities did nothing, so I knocked him out at lunchtime and set his locker on fire for good measure.

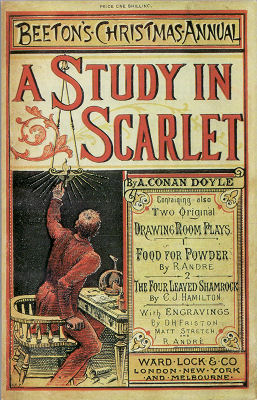

This got me a quick ride to continuation school, where, having finished the semester’s work early (why couldn’t all of high school be self-paced?), I drifted into the small bookstore and picked up A Study in Scarlet.

This got me a quick ride to continuation school, where, having finished the semester’s work early (why couldn’t all of high school be self-paced?), I drifted into the small bookstore and picked up A Study in Scarlet.

This story, which debuted in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887, introduced two young men meeting in a hospital laboratory. “You have been to Afghanistan, I perceive?” asked the taller of the shorter, an army doctor recently returned to England from abroad. Taking rooms in London together, the two became involved in the first of what would become many mysteries. The stories came from young Dr. Doyle while he waited for patients to show up.

The investigative zeal of Holmes, the storytelling of his chronicler, Holmes’s keen insight into human nature, his love of the London underworld (today we would say “shadow”): these and other qualities impressed a future depth psychologist awaiting his first court appearance. Later, while enrolled at Pacifica Graduate Institute, I would learn that Freud had enjoyed the Holmes tales; his case histories read like them.

Much about Holmes and his partnership with the heroic Watson evokes depth psychology. Working over his chemical experiments, a book of arcane secret society symbols near at hand, the figure of the busy detective may well remind us of the alchemist at work in his own private quest. Holmes’s fascination with the dark side of life—he once bragged that being away from London always caused unwonted activity in the criminal class—resembles the clinical curiosity of Janet, Freud, and Jung. Likewise, his willingness to stand by his explorations even when colleagues scorned them. His sense of how apparent misfortunes bring concealed gains to less-than-forthcoming clients anticipates the observational humor of Adler, who told his students never to underestimate what people got out of their symptoms.

Even Holmes’s flaws remind us of the early big three: his unwillingness to promote his own work (Janet), his dabbling with cocaine (Freud), his habit of intellectualizing at the cost of feeling (Freud), his distrust of women (Freud and Jung). These flaws were softened, however, by life events that humiliated and tempered the genius whose early goal was to be little more than a giant brain on legs. Watson’s influence helped there as well.

Even Holmes’s flaws remind us of the early big three: his unwillingness to promote his own work (Janet), his dabbling with cocaine (Freud), his habit of intellectualizing at the cost of feeling (Freud), his distrust of women (Freud and Jung). These flaws were softened, however, by life events that humiliated and tempered the genius whose early goal was to be little more than a giant brain on legs. Watson’s influence helped there as well.

Despite his shortcomings, Holmes also taught us that details matter. “You did not know where to look,” he chides Watson in “A Case of Identity,” “and so you missed all that was important. I can never bring you to realize the importance of sleeves, the suggestiveness of thumb-nails, or the great issues that may hang from a boot-lace.” One might say as much about symptoms, fantasies, mannerisms, dreams, and slips of the tongue of the kind remarked upon by Freud: indicators by which we detect the underlying movements of the psyche.

Holmes also reminded us that we can never know enough: about life, about people, about ourselves. He attempted to master every field, finding, and odd bit of knowledge related to his work as a consulting detective—even to the extreme of identifying from mud splashes where his clients had been throughout London. Read Jung, and this zeal will not seem so far-fetched.

Although I don’t actually consider Holmes an early fictional depth psychologist—as a Victorian rationalist he devalued emotion too much to fit that role—I appreciate what he, his chronicler, and his creator have given us to think about when conducting our own investigations: what to avoid (overconfidence), what to value (relationships, knowledge), what to cultivate (tireless energy).

Most of all, on his birthday we might pause to recall the true source of his greatness: his humanity, which expressed itself largely in his quest for justice for the injured and, more quietly but deeply, in his quiet affection for and loyalty to those near him, especially the redoubtable Dr. Watson.

Yes, they are all fictional creations; but as Jung showed us, these fanciful figures possess their own autonomy too, encapsulating and expressing aspects of the greater Self in everyone.

Craig Chalquist, Ph.D., is Associate Provost of Pacifica Graduate Institute, Founding Editor of Immanence: The Journal of Applied Myth, Story, and Folklore, and author of numerous publications, including the recent book Myths Among Us: When Timeless Tales Return to Life. Learn more at chalquist.com. You can also catch up with Dr. Chalquist in the Certificate in Enchantivism starting April 8, 2019. He will also be one of the instructors for the Certificate for Ecopsychology debuting on Jan. 7, 2019.