A guest post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

When Jonathan Rudow goes into a community to conduct research, he is highly conscious of the fact that he arrives with a particular lens—a lens we each develop individually over the course of our lives evolving from our personal experiences, family values, and cultural conditioning. That lens never allows for the full picture, Jonathan insisted when he sat down with me recently to discuss his work with the Navajo (or the Diné people, as they refer to themselves) at Back Mesa in Arizona. The term “Diné,” meaning—“the people”—is a preferred descriptor for the tribe, Jonathan learned, because in the worldview of the Diné, amongst the many varied animals and “figures” in the world, “the people” are considered just one more of those figures that make up the world. The name “Navajo” was never a name the Diné took upon themselves.

When Jonathan Rudow goes into a community to conduct research, he is highly conscious of the fact that he arrives with a particular lens—a lens we each develop individually over the course of our lives evolving from our personal experiences, family values, and cultural conditioning. That lens never allows for the full picture, Jonathan insisted when he sat down with me recently to discuss his work with the Navajo (or the Diné people, as they refer to themselves) at Back Mesa in Arizona. The term “Diné,” meaning—“the people”—is a preferred descriptor for the tribe, Jonathan learned, because in the worldview of the Diné, amongst the many varied animals and “figures” in the world, “the people” are considered just one more of those figures that make up the world. The name “Navajo” was never a name the Diné took upon themselves.

These are important tenets to consider when one goes into a community very different from one’s own. Jonathan’s doctoral research is focused on how the worldview of certain persons of privilege, including Caucasians, males, or those considered “westerners” in modern culture, can be questioned or even decentralized in order to better understand those individuals and groups who are different from one’s self or experience. No matter who you are, when you come into a community asking questions as a researcher and an outsider—with the possibility of sharing any information you acquire to places in the world where those community members have never been and may never go—it’s critically important to question one’s own motives and approaches in order to be the most inclusive and respectful of both the people and the material, Jonathan points out.

These are important tenets to consider when one goes into a community very different from one’s own. Jonathan’s doctoral research is focused on how the worldview of certain persons of privilege, including Caucasians, males, or those considered “westerners” in modern culture, can be questioned or even decentralized in order to better understand those individuals and groups who are different from one’s self or experience. No matter who you are, when you come into a community asking questions as a researcher and an outsider—with the possibility of sharing any information you acquire to places in the world where those community members have never been and may never go—it’s critically important to question one’s own motives and approaches in order to be the most inclusive and respectful of both the people and the material, Jonathan points out.

Jonathan’s research work among the Diné took place at Black Mesa in Arizona. It’s important to note that “location” is not perceived by the Diné the same way it is for us, Jonathan told me. Location holds a particular weight for them because there are stories attached to place, and these stories are part of their teachings, which are not only educational in nature, but also very spiritual. These stories tend to connect the Diné to very particular places in the landscape, resulting in them being “place-based” people, Jonathan notes. When Jonathan first visited Black Mesa (whose name refers to the coal located there), it was impossible not to respond to what he perceived as the devastation of the communities he encountered, due largely to a significant lack of resources. The availability of water in some areas is a tremendous problem: much of their water has to be fetched from wells that are often far away. Depending on a family’s location, it can take four or five hours to get to a well, Jonathan relates, and then they might spend the rest of the day procuring the water and returning home with it. A family may have to do this weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly, depending on the size of water containers they own. This realization that people “in his own back yard” (not just in far off countries in other parts of the world) did not have access to water, really impacted him during his research.

In our conversation, Jonathan shared historical accounts he has heard from various members of tribe, including the devastation wrought by Indian boarding schools, and by Public Law 93-531 (the Navajo and Hopi Settlement Act¹) which conveniently seemed to displace both Hopi and Diné families who lived right on the line where the coal deposits were found. Much of the destitution evident on the reservation today stems from this Settlement act, according to some accounts. There are also rampant health issues resulting from mining occurring on the reservation. Although much of the water on the reservation is contaminated, many families have no options other than to use the existing water sources for cooking, drinking, and bathing, resulting in ongoing intergenerational health issues from these issues.

In our conversation, Jonathan shared historical accounts he has heard from various members of tribe, including the devastation wrought by Indian boarding schools, and by Public Law 93-531 (the Navajo and Hopi Settlement Act¹) which conveniently seemed to displace both Hopi and Diné families who lived right on the line where the coal deposits were found. Much of the destitution evident on the reservation today stems from this Settlement act, according to some accounts. There are also rampant health issues resulting from mining occurring on the reservation. Although much of the water on the reservation is contaminated, many families have no options other than to use the existing water sources for cooking, drinking, and bathing, resulting in ongoing intergenerational health issues from these issues.

Also in our conversation, Jonathan shared some personal stories about what he observed regarding relationship to the land at Black Mesa, including one about a grandmother in her eighties who still made the arduous journey each year to help plant and harvest the corn in the family plot, and another about his experience of herding sheep for 8-10 hours a day, during which he experienced silence in a way he never had before. That silence, he says, is vitally important to both the culture and language of the Diné. It comes from the land itself, which is truly where they get their language from.

Also in our conversation, Jonathan shared some personal stories about what he observed regarding relationship to the land at Black Mesa, including one about a grandmother in her eighties who still made the arduous journey each year to help plant and harvest the corn in the family plot, and another about his experience of herding sheep for 8-10 hours a day, during which he experienced silence in a way he never had before. That silence, he says, is vitally important to both the culture and language of the Diné. It comes from the land itself, which is truly where they get their language from.

To experience the land there, then, is to experience this stillness of a kind which many of us may never experience Jonathan insists. There is something very moving about that particular kind of stillness that hints at the Diné way of life. The far reaching effects of this experience of silence seems almost magical. Even listening to Jonathan talk about it, I realized I felt more connected; more woven into a tapestry of being that we don’t often notice in our busy lives. It’s something that’s profoundly missing in our culture. When I asked Jonathan about conclusions coming from his research, Jonathan points to the value of a lack of conclusions. Through the research, he feels he was able to step back from the very personal lens he brought into the experience with him. There’s a preconceived, romanticized version researchers can hold which played a role in actually steering him away from pursuing traditional research at Black Mesa. Some of the serious questions he asked in the early part of his work “came back in his face” and “hung in the room in this really uncomfortable way” because they weren’t real, he relates. “The stark silence and truthfulness with which they approach each other and the world and language and you kind of evaporates the rest of those things and it just becomes words,” Jonathan says. What matters is not the questions, but the issues at hand.

What the people you’re researching really need is for you to be in the room with them, to know if you are there in a way that can help, he believes. Perhaps the best thing that came from his research was the disillusionment of his approach to research and a new understanding that the most heartfelt way to move forward is to just show up in a human and authentic way and simply ask, “How can I help?”

Jonathan notes a shift in the relationship between outsiders and the people on the reservation these days, especially through organizations like Black Mesa Indigenous Support who are now allowing and inviting people from outside their circle to come in and experience life and the issues they are facing. In one interview, Jonathan even went as far as to ask how they felt about outsiders coming in. Right now, outsiders seem to be welcomed, in part due to the technology (like video cameras) that they bring with them that can help the cause of the Diné document injustices (such as when a SWAT team swoops in to remove a large part of their sheep due to a supposed infraction against a law that limits the number of sheep they can have in a herd). In such situations, the Diné perceive that outsiders with video cameras can play a useful role and they are increasingly welcoming those who can help them have a voice, instead of stripping them of their voice as has so often been the case.

Jonathan notes a shift in the relationship between outsiders and the people on the reservation these days, especially through organizations like Black Mesa Indigenous Support who are now allowing and inviting people from outside their circle to come in and experience life and the issues they are facing. In one interview, Jonathan even went as far as to ask how they felt about outsiders coming in. Right now, outsiders seem to be welcomed, in part due to the technology (like video cameras) that they bring with them that can help the cause of the Diné document injustices (such as when a SWAT team swoops in to remove a large part of their sheep due to a supposed infraction against a law that limits the number of sheep they can have in a herd). In such situations, the Diné perceive that outsiders with video cameras can play a useful role and they are increasingly welcoming those who can help them have a voice, instead of stripping them of their voice as has so often been the case.

How can the field of depth psychology be informed by the people of Black Mesa, I wonder to Jonathan, who has a ready answer: It is tied in to the collective unconscious—the anima mundi, the soul of the world. Now is a critical moment in history, he believes, and there’s a lot being said through indigenous people as well as in other groups that have been marginalized—including those of Black Lives Matter² and the growing gathering at Standing Rock in North Dakota to protest a proposed oil pipeline³. At Black Mesa, they are not just speaking up for the environment, they are also voicing the concerns of the collective unconscious, and that really needs to be heeded and followed, Jonathan ascertains. Through depth psychology we can learn to deconstruct some of the original ways we view issues, and we can gain entrance to the collective unconscious which leads to better understanding of the unity of all things and people. As depth psychologists, we can contribute mainstream platforms that will allow those voices to be heard.

In closing, Jonathan spoke poignantly about his experience of silence at Black Mesa, which “gives a sense of living.” We often strive to find words for things (sometimes lots of words), he notes, but it is appropriate only when there has been a certain amount of silence first. In our culture there’s a continuous urge to fill the void in our conversations and our lives with words in an attempt to “find our way down to an authentic foundation”—but this is simply not the way to gain access. There’s so much wisdom that can come from just being in silence, he says. That's perhaps the most important lesson from these cultures, because when you’re silent, that’s when you can hear those other voices speak.

Listen to the full audio interview with Jonathan Rudow, M.A. here (approx. 39 mins):

Find out more about the Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology, and Ecopsychology (CLE) specialization at Pacifica and how students in this program are working with communities and organizations that they are passionate about.

Learn more or get involved with the Navajo/Diné at Black Mesa: http://supportblackmesa.org/

Learn more about the Sristi Village in India: http://www.sristivillage.org/

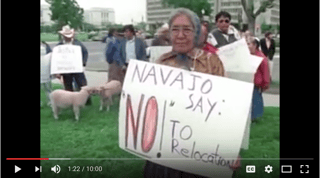

(Photo credit: Woman with sign is from the video documentary Broken Rainbow, Part 1)

¹ See more in this document, “The Impact of the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act of 1974 by the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission”

² Learn more about the Black Lives Matter movement: http://blacklivesmatter.com

³ Read an NPR report on the Standing Rock protests -->

You can read an essay from Bonnie’s own Pacifica fieldwork, "The Power of Story and Place among the Navajo in Canyon de Chelly" at http://www.depthinsights.com/Depth-Insights-scholarly-ezine/toc-depth-insights-scholarly-e-zine-issue-1-fall-2011/the-power-of-story-and-place-among-the-navajo-in-canyon-de-chelly-by-bonnie-bright/

Jonathan Rudow is working towards his Ph.D. in Depth Psychology with specialization in Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology, and Ecopsychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute. His work has brought him into communities such as the Black Mesa reservation land in Northern Arizona, where he spent several weeks working with the Dineh to learn more about their current struggles and ways in which they persist despite ongoing colonial and industrial onslaught; as well as the Sristi Village near Pondicherry, India, where he was able to work alongside persons of varying abilities who are working together to build a more inclusive lifestyle for themselves and their community. Jonathan is conducting dissertation research focused on deciphering a methodology for de-centralizing the worldviews of persons of privilege, pinpointing Caucasian American males who are straight and neuro-typical, for the purpose of better understanding their parts in creating a more equitable and tolerant future.

Jonathan Rudow is working towards his Ph.D. in Depth Psychology with specialization in Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology, and Ecopsychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute. His work has brought him into communities such as the Black Mesa reservation land in Northern Arizona, where he spent several weeks working with the Dineh to learn more about their current struggles and ways in which they persist despite ongoing colonial and industrial onslaught; as well as the Sristi Village near Pondicherry, India, where he was able to work alongside persons of varying abilities who are working together to build a more inclusive lifestyle for themselves and their community. Jonathan is conducting dissertation research focused on deciphering a methodology for de-centralizing the worldviews of persons of privilege, pinpointing Caucasian American males who are straight and neuro-typical, for the purpose of better understanding their parts in creating a more equitable and tolerant future.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.