A guest post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

There is a certain kind of transformational process that demands the most and the best of us so that we can respond to traumatic situations, just as military, veterans, and first responders do on a daily basis. From a depth psychological perspective, this kind of transformation can be initiated through a psycho-mythic journey to warriorhood, believe Ed Tick and John Becknell, who offer archetypal and depth psychological frameworks for military, veterans, and first responders, including police officers, sheriff departments, border patrol, firefighters, paramedics, EMTs (Emergency Medical Technicians), and dispatchers and other individuals who take emergency calls.

There is a certain kind of transformational process that demands the most and the best of us so that we can respond to traumatic situations, just as military, veterans, and first responders do on a daily basis. From a depth psychological perspective, this kind of transformation can be initiated through a psycho-mythic journey to warriorhood, believe Ed Tick and John Becknell, who offer archetypal and depth psychological frameworks for military, veterans, and first responders, including police officers, sheriff departments, border patrol, firefighters, paramedics, EMTs (Emergency Medical Technicians), and dispatchers and other individuals who take emergency calls.

Tick and Becknell consciously engage the term “warrior” to distinguish the archetypal role of those who dedicate themselves to the preservation and protection of society, often in the face of great danger. The Warrior archetype has appeared in mythology and sacred writings for thousands of years, notes Tick, and it has been a dominant archetype and psychological and social role in modern society as well.

Tick and Becknell consciously engage the term “warrior” to distinguish the archetypal role of those who dedicate themselves to the preservation and protection of society, often in the face of great danger. The Warrior archetype has appeared in mythology and sacred writings for thousands of years, notes Tick, and it has been a dominant archetype and psychological and social role in modern society as well.

While the U.S. military has also turned to the word “warrior” over the past several years as a term meant to bestow honor on anyone who has served in the military or in a war zone, Tick and Becknell contend that warriorhood is a sacred idea that goes beyond the parameters of physical service. Instead, it is a form of initiation going back thousands of years. It requires undertaking a lifelong “warrior’s journey”—a psycho-spiritual passage that allows a warrior to carry the pain and suffering they have observed while in service without falling victim to devastating impact on the psychological self as a result.

If an individual in the armed forces has been harmed physically, psychologically, or spiritually, the military might refer to them as a “wounded warrior,” Tick points out, but the military does not go so far as to complete the initiation process so their warriors can come home and carry the experience with meaning, honor, dignity, and without suffering personal psychological or spiritual distress or devastation due to what they have experienced in the field.

If an individual in the armed forces has been harmed physically, psychologically, or spiritually, the military might refer to them as a “wounded warrior,” Tick points out, but the military does not go so far as to complete the initiation process so their warriors can come home and carry the experience with meaning, honor, dignity, and without suffering personal psychological or spiritual distress or devastation due to what they have experienced in the field.

From this perspective, it is possible to view the condition commonly called PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) as an interrupted and incomplete initiation on the warrior’s journey—a process that needs to be extended in order to provide context and complete the initiation, so that those who have suffered because of the experiences they have encountered during their service can make meaning of it.

What we call PTSD today has always existed as part of humanity, Tick affirms. It appears in the Bible, in mythology, and in historical records from ancient times. However, until relatively recently, it was not considered a psychological disability that required an individual to be separated from the rest of society and treated by specialists. Indigenous cultures from around the world gave this kind of wounding spiritual names, for example. The condition, translated from the Lakota language, means “The spirits left him,” Tick reveals. When Lakota warriors experienced this condition, they were considered spiritually bereft, and so their medicine people conducted spiritual intervention and offered support from both an individual and community standpoint so the spirit of the warrior could be restored.

In their work, Tick and Becknell treat this wounding as an archetypal condition—as a portal or doorway into cosmic dimensions whether one is in a war zone, fighting a fire, or in the inner cities combatting violence. They teach that the traumatic situation itself is a cosmic, archetypal condition, and whenever an ordinary human being enters into it, he or she is inevitably and irrevocably transformed.

The vast majority of first responders would never be in a position to be diagnosed with classic symptoms of PTSD, Becknell states, but every one of them is changed by the work that they do. Often we assign only two options to those individuals who have undergone transformation due to their experiences. Ultimately, they are either “mentally ill”—they have the symptoms of what is deemed “psychopathology”—or they are “OK.” Simply because one has an experience doesn’t mean that they are mentally ill, Becknell persists. When it comes to our warriors, we can no longer afford to judge people because they are responding to an experience, but as a society, we have simply not found an effective way to talk about these changes that take place.

To this end, rather than focusing on wounding or on diagnoses rooted in psychopathology in veterans and first responders, Tick and Becknell take a holistic approach, exploring communal and psycho-spiritual factors in service of helping warriors integrate and heal. The solution is to find new ways to talk about—which are actually old ways of talking about it, Becknell insists. Hard experiences often leave the first responder or veteran bereft of meaning. The process of finding meaning always takes us into mythology. Mythic thinking helps provide a framework for “what is incomprehensible.” After a traumatic experience, we look for a context, not for psychopathology. What we’ve lost through modern society is our capacity to look at things through a mythic lens.

What Tick and Becknell teach, both together and separately, is a World Warrior tradition, an understanding of the Warrior archetype, and how to frame experiences using a mythic and depth psychological approach. Retreats such as the upcoming program at Pacifica replicate the warrior’s journey home as it is practiced universally around the world.

As both facilitators have worked internationally, they have observed and experienced the warrior archetype firsthand in many cultures. It’s impossible to make it academic, coming from their heads for people who have experienced violence and trauma from their bodies, spirits, and entire beings, Tick acknowledges. In studying world warrior traditions and world cultures, they have found that there are archetypal, universal conditions that occur, making it necessary for the warrior to return home through applied communal ritual practice. While some rituals vary, the underlying principles are the same. All warriors need community support when they come home. Rather than being diagnosed and isolated, they need to be brought into the center of the community and surrounded and protected by those whom they were serving and protecting while they were in the field. They need purification, cleansing, affirmation, and time for tending and integration. They need to tell their stories to the entire community. In warrior return, there needs to be restitution where the community accepts the moral responsibility and burden that the warrior has been carrying alone.

Starting May 11, 2017, Tick and Becknell co-led a two-session program at Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara, CA, called “Holistic Tending for Military, Veterans, and First Responders—Psycho-spiritual and Communal Support and Healing of Violent Trauma, Moral Injury and Stress,” an academic and experiential educational experience that builds on their pioneering work in the military, veteran and first responder fields. The program was delivered in two separate four-day sessions) using lecture, discussions, and experiences to lay a foundation and offer a hands-on practicum for a holistic and communal approach.

Unlike some other programs that aim to serve the psychological needs of warriors, veterans, and first responders—as well as the individuals and communities that support them, the program led by Tick and Becknell did not focus on wounds. Rather it sought to understand how to create the social conditions and a framework in society, enabling us to tend to the needs of veterans and first responders. This kind of work can change cultures within first responder, organizations, and within the military, as well as within society, so they can begin to view it differently, Becknell maintains.

When Tick and Becknell considered the best place to offer a program for focusing on soul work with military and first responders, Pacifica was an obvious choice. Pacifica is recognized as a “world center for archetypal and mythological studies and for going deep,” Tick affirms, and the Pacifica Retreat Center—in combination with Pacifica’s commitment to tending the soul of the world—makes it the perfect container in which Tick and Becknell can bring archetypal work into challenging real world for warriors and those who want to support them.

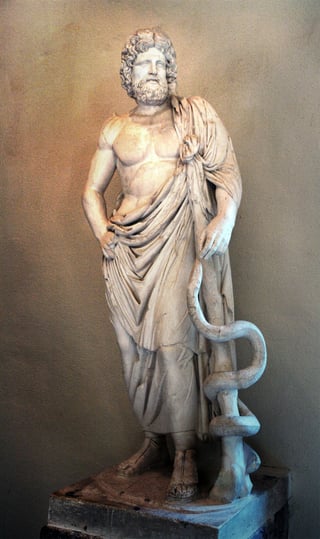

When it comes to PTSD, dreams—and especially nightmares—can become especially active, even creating fear of sleeping in some individuals who return to places of combat in their dreams over and over again. Warriors are “drenched in the death imprint,” having observed or attended to death in ways and to a degree that non-warriors don’t, Tick asserts. From a spiritual perspective, dreams are archetypal messages from the spirit world to be utilized in the healing process, and the dead that appear in dreams may be viewed as the souls of the fallen who want to communicate. Rather than trying to suppress difficult nightmares, warrior work trains warriors to engage and respond to what the dreams are asking in order to embrace what is trying to return to the warrior. Tick, who has taken warriors to Greece to do Asklepian dream incubation (rooted in the mythology of the Greek god of medicine and the healing arts, Asklepius[1]), notes that this type of soul work has been especially effective in healing—so much so that some warriors have reported having combat nightmares all night long but “returned” in the morning feeling completely liberated and cleansed, never having combat nightmares again.

When it comes to PTSD, dreams—and especially nightmares—can become especially active, even creating fear of sleeping in some individuals who return to places of combat in their dreams over and over again. Warriors are “drenched in the death imprint,” having observed or attended to death in ways and to a degree that non-warriors don’t, Tick asserts. From a spiritual perspective, dreams are archetypal messages from the spirit world to be utilized in the healing process, and the dead that appear in dreams may be viewed as the souls of the fallen who want to communicate. Rather than trying to suppress difficult nightmares, warrior work trains warriors to engage and respond to what the dreams are asking in order to embrace what is trying to return to the warrior. Tick, who has taken warriors to Greece to do Asklepian dream incubation (rooted in the mythology of the Greek god of medicine and the healing arts, Asklepius[1]), notes that this type of soul work has been especially effective in healing—so much so that some warriors have reported having combat nightmares all night long but “returned” in the morning feeling completely liberated and cleansed, never having combat nightmares again.

Becknell engages the concept of the imagination in warrior work with first responders, and views dreams as “the sleeping work of the imagination.” It is with our imagination that we continue to make sense out of life, he points out, and imagination can be wounded. Imagination enables us to remember the past and conceive of the future, so it is critical in helping us each build a story about our life so that we can make meaning of it. Since one of the ways the imagination can manifest itself is in dreams, bringing awareness of the power of working with dreams to first responders can be very revealing for them, he notes.

Ultimately, the goal of working with first responders and veterans is not about trying to “help” them. Each warrior has real gifts that are very much needed at this critical juncture in our culture. Because of what they have experienced at the “edge,” they have a “much sharper sense of what really matters, and a much sharper sense of what a healthy society might look like,” insists Becknell, and they bring back valuable information we need in our society today. Therefore, a key part of the work related to warriors is to wake up civilian society and help them realize not only do the warriors protect and serve, but they also have great experience and insights from the borderlands.

We are all affected by potential danger and by the threat or impact of war, whether it’s conscious or not, so it seems clear to me that the work Tick and Becknell are doing to help heal the warrior community can’t help but ripple out to affect all facets of our society. And, while some military and first responders may be the first to shy away from the terms “warrior” or “hero,” which they feel paints them larger than life, according to Becknell, these archetypal ideas are not labels, but rather doorways to finding well-being and to tending soul along with the wounds that come naturally with the work that these individuals take on. Only then can they embrace the richness and fullness of the archetypal warrior, and the strength and wisdom inherent therein—including in the wounds they’re carrying. As they do, their identity expands, and they experience a joy that is bigger than their wounds, carrying pride, dignity, meaning, and desire for further service, instead of despair.

Listen to the full audio interview with Ed Tick, Ph.D. and John Becknell, Ph.D. here (approx. 47 mins):

Learn more about Soldiers Heart at www.soldiersheart.net

“Holistic Tending for Military, Veterans, and First Responders—Psycho-spiritual and Communal Support and Healing of Violent Trauma, Moral Injury and Stress” was offered in late spring of 2017. To learn more about this particular program, please visit www.retreat.pacifica.edu

[1] Read more about Asklepios at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asclepius

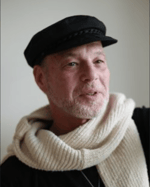

Edward Tick, Ph.D. is an internationally recognized transformational healer, psychotherapist, writer, educator, and poet. Co-Founder and Director of Soldier’s Heart, he has been working with veterans and other survivors and developing holistic, spiritually and culturally based trauma healing for over forty years. Dr. Tick works internationally on the psycho-spiritual and cross-cultural healing of military, war and violent trauma and on holistic and spiritually-based healing. He has served as the U.S. military’s subject matter expert trainer on healing Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Moral Injury for the Army, Air Force National Guard and Special Operations chaplain and behavioral health corps and wounded warrior programs. Dr. Tick is the author of six books including the groundbreaking and award-winning War and the Soul. His newest publications are Warrior’s Return and the audio set Restoring the Warrior’s Soul.

Edward Tick, Ph.D. is an internationally recognized transformational healer, psychotherapist, writer, educator, and poet. Co-Founder and Director of Soldier’s Heart, he has been working with veterans and other survivors and developing holistic, spiritually and culturally based trauma healing for over forty years. Dr. Tick works internationally on the psycho-spiritual and cross-cultural healing of military, war and violent trauma and on holistic and spiritually-based healing. He has served as the U.S. military’s subject matter expert trainer on healing Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Moral Injury for the Army, Air Force National Guard and Special Operations chaplain and behavioral health corps and wounded warrior programs. Dr. Tick is the author of six books including the groundbreaking and award-winning War and the Soul. His newest publications are Warrior’s Return and the audio set Restoring the Warrior’s Soul.

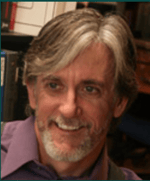

John Becknell, Ph.D. is a community psychologist and works with first responders, first responder agencies, and communities throughout the United States promoting a holistic approach to the psycho-spiritual impact of emergency work. John has been involved with emergency services for more than 40 years. As a paramedic for 18 years he worked in a variety of settings including the Middle East and Central America. He is the former editor-in-chief of the Journal of Emergency Medical Services and has published in numerous journals and magazines. He is the former board chairperson for Soldier’s Heart, Inc. and leads retreats for first responders, veterans and civilian society. His on-going work and research focuses on the unique and necessary relationship between communities and their first responders and veterans.

John Becknell, Ph.D. is a community psychologist and works with first responders, first responder agencies, and communities throughout the United States promoting a holistic approach to the psycho-spiritual impact of emergency work. John has been involved with emergency services for more than 40 years. As a paramedic for 18 years he worked in a variety of settings including the Middle East and Central America. He is the former editor-in-chief of the Journal of Emergency Medical Services and has published in numerous journals and magazines. He is the former board chairperson for Soldier’s Heart, Inc. and leads retreats for first responders, veterans and civilian society. His on-going work and research focuses on the unique and necessary relationship between communities and their first responders and veterans.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.