A guest post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

Lisa Pounders has always had an interest in art and poetry, and has long been inspired by the work of Joseph Campbell—even painting his directive, “Follow your own bliss” above a window in her art studio years ago. Her story is not unlike that of others who have attended Pacifica Graduate Institute: when she enrolled in the Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life program, she felt she was responding to a “mysterious sense of calling” that many other students and alumni have also reported. Her own sense of summons had to do with the sense that creativity and what she initially learned about C. G. Jung’s ideas about the unconscious were intrinsically linked. Making the connection explicit (especially through a Master’s degree in Creativity) seemed a powerful way to move her own life forward.

Discovering that Campbell’s library was housed at Pacifica was one of the “threads” that also led her to her decision. Now pursuing her Ph.D. in the Jungian and Archetypal Studies specialization at Pacifica, Pounders has a much better understanding of the relationship between art and depth psychology. One aspect lies in Jung’s idea of individuation, a process by which there is an inner drive toward a calling or a sense that there’s something bigger at work in our lives—not “fate,” Pounders insists, but “ways to develop and to enrich your life, and perhaps to enrich other people’s lives.” That initial quote from Campbell, “Follow your own bliss,” was her personal call to art, Pounders reveals, and from there she was led to Pacifica.

As she began her exploration of depth psychology at Pacifica, Pounders found herself excited about Jung’s idea that the unconscious is inherently creative. The drive toward development has a force for making and for image-making, as well, a tenet Jung discovered on his own when he started working on his Red Book in the years after his fallout with Sigmund Freud. Once Jung found himself on his own, he turned to the process of what he called “active imagination” to drop down into the unconscious to have dialogues with inner images and characters that revealed themselves to him. He used both writing and painting or drawing in the process of active imagination. The resulting illustrations now highly publicized in The Red Book came from a state that might be described as dreaming in a semi-conscious state. Jung described the process that contributed to The Red Book as his “confrontation with the unconscious,” and many of his theories can be traced back to their origins during those years when he was so engaged in that confrontation that ultimately resulted in the Red Book.

The way that Jung engaged with images as living images was, in part, a catalyst for Pounders to write an article entitled “Transformation Through Art: Exploring Jung’s View of Art and the Relevance of Charlotte Salomon’s ‘Life? or Theater?’ ”¹, recently published in the International Jungian of Jungian Studies. Though Charlotte Salomon, a German Jewish woman, tragically perished at Auschwitz in 1943 when she was barely 26, she first created an opus called “Life? or Theater?”—which has gained wide acclaim.

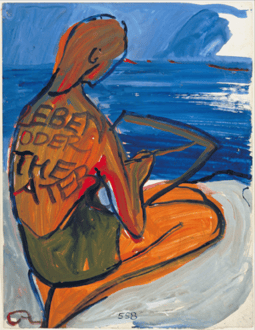

|

| This work is the concluding page of Charlotte Salomon's principal work Life? or Theatre?. The final gouache harks back to the text that begins the work describing Salomon sitting beside the sea painting. A tune enters her mind and she starts to hum it. As she hums, she realises the tune matches what she is painting…Salomon completed the work at the Hotel "Belle Aurore", Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat in summer 1942 (the proprietor later recalled her humming while she worked). |

The format for “Life? or Theater?” is unusual. Though it exists in book form, it originated from a manuscript with 769 paintings, written text, and unique transparent overlays that contain directions for music. Charlotte Salomon referred to the work in German as a singspiel or song-play, a form of opera², and imagined people looking at the paintings, reading the text, and humming the music as they moved through the work. The multi-media work was fictional, yet also based on her life—resulting in a complex, semi-autobiographical work of someone going through World War II who ultimately was murdered in the Holocaust. Somehow, Salomon’s work survived.

Part of the opus involved Salomon working through a “plague of suicides” in her family, Pounders told me, including the deaths of Salomon’s aunt, mother, and other close family members by their own hands³. It seems clear that art can serve as vehicle to help us work through trauma, and Salomon’s work on “Life? or Theater?” may indeed be key to Salomon not following through on that same impulse to suicide that possessed so many of the women in her family.

Pounders first came across Salomon’s work in 1997, long before she came to Pacifica, after stumbling on an article in Time magazine about an exhibit of Salomon’s images in the United States, as well as a biography about Salomon by Mary Felstiner[4]. At the time, Pounders suggested the book, To Paint her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era (1997) for the book club she was involved in. She also happened upon a bound copy of “Life? or Theater?” (entitled Charlotte (1981)) in a used book store. While that version lacked the music overlays, it was the closest representation Pounders had seen of the original work in book form.

Pounders first began to discern a connection between the work of Salomon and the work of Jung while at Pacifica, in a class in the Engaged Humanities program on creativity and activism. She couldn’t stop thinking about how Charlotte Salomon had asserted her own existence through her work on “Life? or Theater?” in the face of Nazi oppression, something that occurred to Pounders as a profound act of activism when she really thought about it. Jung’s Red Book was introduced as another multi-media work, and a method by which Jung worked through his own inner turmoil. While Charlotte Salomon created her book in 1940, and Jung worked on his from 1913 until around 1930, both individuals were working through wars: Jung beginning his just before the first world war, and Salomon commencing hers during World War II.

Patterns and synchronicities tend to draw us in, often bring wisdom, understanding, and healing, and art can work on us in unexplained ways, even without our conscious knowing. Pounders notes that art can work us by way of symbols, and Jung was a big proponent of the idea that symbols (and corresponding archetypes) worked as portals to the unconscious. While some symbols can point to something known, many remain mysterious. Archetypes, as patterns that inform our lives, are recognizable in art and also in non-visual places that stem from creativity itself. They speak to us in both conscious and unconscious ways.

|

| Charlotte Salomon painting in the garden at Villa L'Ermitage, Villefranche-sur-Mer, about 1939. |

Part of the power of Charlotte Salomon’s work—and Jung’s Red Book, too—was the use of images, words and even music to try to express what’s happening inside for one’s self, and also to communicate to other people, Pounders suggests. There is a “third kind of thing” between you and your unconscious that also allows it to “get out there” where others can also connect to it. When working with art, we’re always working with pieces of ourselves, she asserts. In fact, Pounders, herself, can identify times in her own life when she was trying to paint more than a simple narrative; attempting to capture something beyond. She maintains a notebook of her own in which she creates mandalas and other art that doesn’t necessarily have a narrative to it, but through which she works with unconscious contents.

Hearing this prompts a memory for me of reading about how some mid-Plains Indians have practiced the creation of objects that represented their dreams so that they could bring the dream into form and convey the immediacy of the sacred into the world, expressing the power of the dream itself through the object they had made[5].Those individuals likely didn’t care if they were ‘artists” or not, I realized: more probably, they only cared to allow the dream to speak through them via the object they created. Art is sacred; art is speaking; art does have its own voice and its way of getting out into the world

Jung had the same experience, Pounders relates. Sometimes practitioners of Jungian or depth psychology try too hard to analyze the images that emerge from dreams or elsewhere in the unconscious. Jung believed in allowing the images coming forward to him to have their own autonomy. While in the process of engaging the dream through drawing or painting, he literally asked, “What is it that I’m doing?” and the answer came through a female voice, “It is art.” Today we can see that forms have their own energy and potential. Though Jung was very focused on the scientific aspects of psychology, art has its own way of expressing itself and dialoguing with us. It also has its way of connecting us culturally as well as personally.

|

| Charlotte Salomon, self-portrait (1940). Institution: Collection Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam. Photo © Charlotte Salomon Foundation (Public Domain)[6] |

I remember someone writing once that artists are on the forefront of the revolution, painting or creating imagery around what is coming in the future. If we’re willing to make space for that creative function, it results in waves that can also change the culture—just as it did with Salomon and, of course, with Jung as well.

There is an element of synchronicity and endurance around Salomon’s work. At a time when things seemed rather hopeless, and restrictions were growing for Jewish citizens in Germany, Charlotte Salomon was able to get into an art school and start painting, Pounders reminds me. Though eventually Salomon had to drop out as the situation became more critical, Salomon’s work was a way to express the importance of her life, and indeed, it rippled out on a multitude of levels. It revolved around the feminine voice, racial issues, and also creativity, Pounders insists, and those aspects of her work still speak to us today. Pounders’ future research will center on the connection to Jung’s Red Book and the role of the feminine in the work of both Jung and Charlotte Salomon. I personally look forward to learning more.

Listen to the full audio interview with Lisa Pounders, M.A. here (approx. 28 mins)

Learn more about the Engaged Humanities & the Creative Life M.A. program at Pacifica

Find out more about the Jungian and Archetypal studies specialization at Pacifica

[1] “Transformation Through Art: Exploring Jung’s View of Art and the Relevance of Charlotte Salomon’s Life or Theater?” by Lisa A. Pounders, International Jungian of Jungian Studies, February 2016

[2] Singspiel is a German music form resembling "operetta" in some respects, although actors’ parts are often spoken over, rather than sung with the music. Music provides the backdrop for the play-form which is most often comical in nature, tragedy being a less-frequent motif. Note that Salomon’s spelling, "Singespiel", is off by an ‘e’, but whether this was intentional of not is unclear: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Salomon#Singespiel__.5Bsic.5D

[3] See the history of suicides in the family of Charlotte Salomon at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Salomon

[4] Biography by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner, To Paint Her Life. Harper Collins, 1994

[5] (See The Dream Seekers: Native American Visionary Traditions of the Great Plains—Lee Irwin: http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/490389

[6] Jewish Women's Archive. "Charlotte Salomon, Self Portrait, 1940: https://jwa.org/media/salomon-charlotte-still-image

Lisa Pounders, M.A. completed her MA in Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life from Pacifica Graduate Institute in 2014. She is currently a third-year student in their PhD in Depth Psychology with Specialization in Jungian and Archetypal Studies program. In 2016 her first peer-reviewed article was published in the International Jungian of Jungian Studies. Lisa works as a mentoring psychologist, instructor, visual artist, and poet, and is currently transiting between her hometown of Asheville, North Carolina and the high desert of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Lisa Pounders, M.A. completed her MA in Engaged Humanities and the Creative Life from Pacifica Graduate Institute in 2014. She is currently a third-year student in their PhD in Depth Psychology with Specialization in Jungian and Archetypal Studies program. In 2016 her first peer-reviewed article was published in the International Jungian of Jungian Studies. Lisa works as a mentoring psychologist, instructor, visual artist, and poet, and is currently transiting between her hometown of Asheville, North Carolina and the high desert of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.