Racism, Cultural Violence, and Conscious Change: How The Truth Telling Project is Transforming Society

An Interview with The Truth Telling Project Co-Founder, David Ragland, Ph.D.

A Guest Blog Post by Bonnie Bright, Ph.D.

Historic African American Malcolm X, leader who spoke out for black nationalism famously said, 'I'm for truth, no matter who tells it. I'm for justice, no matter who it is for or against.” This quote, featured on the home page for The Truth Telling Project speaks volumes about the mission of this unique and important organization.

The Truth Telling Project is a grassroots initiative that focuses on how communities can tell their stories, reports David Ragland, Ph.D., who grew up a few miles from Ferguson, Missouri, a city that became famous in the wake of the fatal shooting of 18-year-old African American Michael Brown by white police officer, Darren Wilson, in August 2014, and the ensuing riots it instigated [1]. The resulting protests soon led to a nightly curfew and a militarized response by law enforcement.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, The Truth Telling Project evolved to share local voices, educate America, and eliminate structural violence and systemic racism against Black people in the United States [2]. Dr. Ragland, who is speaking at Pacifica’s upcoming Jung conference, “Response at the Radical Edge: Depth Psychology for the 21st Century,” is the Co-founder and Co-director for The Truth Telling Project of Ferguson, as well as an Assistant Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, The Truth Telling Project evolved to share local voices, educate America, and eliminate structural violence and systemic racism against Black people in the United States [2]. Dr. Ragland, who is speaking at Pacifica’s upcoming Jung conference, “Response at the Radical Edge: Depth Psychology for the 21st Century,” is the Co-founder and Co-director for The Truth Telling Project of Ferguson, as well as an Assistant Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies.

The Truth Telling Project was established in part for political efficacy, so that communities can have their own voice and create a narrative, Ragland maintains. What happened to Michael Brown in Ferguson happens all over the country. While many people in the U.S. have family members who have been brutalized or killed by police, their stories are not being told as they should, or are even being erased in some cases.

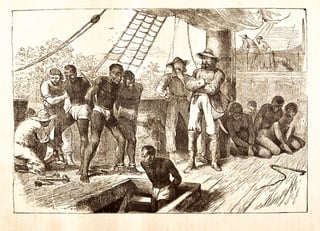

In our society, we want to believe that things are fair and everyone has an equal shot, but it’s simply not true, Ragland submits. Stories that come from the people are a kind of truth that reveals what the American landscape really looks like, and police violence against African Americans is just the tip of the iceberg. Racism and causes of police violence are historical, are deeply rooted in our society, and are even an aspect of intergenerational trauma, he insists, noting how legal scholar and civil rights advocate, Michelle Alexander, writes about prisons as extensions of slavery in her 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration and the Age of Colorblindness [3].

Society has short-term memory and is silent on issues of identity, says Ragland. We are primarily an assimilationist society; that is, the only way people can make it is to be quiet and fit in in order to be part of it, but the structural issues of racism make it virtually impossible to integrate. It doesn’t help matters that the Ferguson police department, along with many law enforcement organizations in the U.S., derive a large part of their budgets from targeting people of people of color, which is not certainly not conducive to change, he adds.

Storytelling empowers people to action because they are such a basic aspect of who we are. The stories we tell, experiences we’ve had, and the communication of these stories are a core part of our experience, and every community has its own stories, which ultimately amount to its culture. Many communities have a culture of violence, Ragland reflects. Police violence reflects that: it tells a story about who is able to will the violence; who is always guilty or always, correct, etc. When violence is perpetrated on people of color, especially black people, they are too often perceived as criminals while the police are perceived to have the “truth.” The work of The Truth Telling Project, then, is about re-situating truth. It’s “people-powered”; that is, truth can come from people and that kind of truth is often the truest.

One course of action The Truth Telling Project took was to hold hearings where people in the community were allowed to speak freely. While most processes involving transitional justice [4] seeks testimony from multiple sides, these particular hearings focused on listening to voices from the community and not from law enforcement, because when people are traumatized by police, how do you speak freely when police are in the room, Ragland points out.

Stories about our families help us reach out and connect with who we perceive as the "other.” For example, Ragland relates how Michael Brown’s mother attended a hearing of the Human Rights Commission in Geneva, Switzerland, and at one point had the opportunity to tell her story, describing what it felt like to stand by on a hot August night in Missouri, overhearing police making jokes about her dead son’s body as it lay in the street for over four hours. When she spoke, people stopped and listened in a way they had not listened before, Ragland notes.

When The Truth Telling Project invited people from the community to tell their stories at the hearings, they had to create their own process from the ground up. It didn’t fit with traditional Truth and Reconciliation processes where the state gets involved, because in this case, the state was a primary perpetrator against black people. How do you call on the state to finance and legitimize a process when they play a role in the trauma that has been perpetuated, Ragland asks. Meanwhile, the initiative has garnered visibility and support from some dedicated and high-profile activists, including Fania Davis, a civil rights lawyer who is the sister of actress Angela Davis [5]; Bernard Lafayette, Jr., a prominent figure in the Civil Rights Movement; Michael Brown, Sr.; Momma Cat (Cathy Daniels) [6]; and activist Ebony Williams, among them.

Meanwhile, Ragland and others involved in The Truth Telling Project have learned from similar organizations, including the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation process, who helped them come up with a mandate and structure. From the beginning, The Truth Telling Project has strove to communicate stories within the context of their own culture and ritual.

One thing that has come out of the work is political efficacy, Ragland observes. They are educating the community to understand it is not only their right, but also a necessity to speak up so others can hear. To this end, the initiative has live streamed video, organized study groups and a built a curriculum so people could learn from the stories that are shared. Instead of completing a traditional report for the project, they have decided launch an online learning archive platform that guides users to understanding the structural issues brought up in the stories. The brother of Tamir Rice, a 12-year old African American boy who was shot dead by police in Cleveland [7], talks about the deep militarization of police, for example, and how police are empowered to use weapons against anyone they decide is a threat, whether others would deem it a threat or not. Others involved in the work have run for political office and are getting visibility and endorsements.

In our society most people aren’t empowered to share their story, especially as a black person, Ragland reminds me. Now many of these previously untold stories from individuals and communities that have been marginalized in the past are housed in the Library of Congress for perpetuity. Our society may not yet be ready for a Truth and Reconciliation process that deals with past historical harms, nor those that continue through economic policy, criminal justice, and law enforcement, he persists, but with them archived in a safe and prominent location, we are far less likely to forget, especially in America where we have a tendency toward forgetting, silencing, or even changing the story.

One example where the story was changed involved a McGraw-Hill Texas textbook that called slaves who were stolen against their will “workers” who were transported to the U.S., effectively erasing the word “slavery” from the scenario [8]. If we don’t remember such stories, we’ll repeat them, Ragland insists, and that’s a critical issue today. Unfortunately, some people are now drawing historical comparisons with the current administration and rhetoric in the U.S. with some of the most regrettable moments in history that brought out worst in everyone.

One example where the story was changed involved a McGraw-Hill Texas textbook that called slaves who were stolen against their will “workers” who were transported to the U.S., effectively erasing the word “slavery” from the scenario [8]. If we don’t remember such stories, we’ll repeat them, Ragland insists, and that’s a critical issue today. Unfortunately, some people are now drawing historical comparisons with the current administration and rhetoric in the U.S. with some of the most regrettable moments in history that brought out worst in everyone.

Ferguson was a “flashpoint”: It gained attention because it was a new kind of activism that people hadn’t seen before, Ragland says, citing multiple injustices that led to the outcome. Police used a taser on a black woman who was a school board member, for example. Tear gas, the same kind employed against Palestinians in Gaza, was used by police in Ferguson during the riots. Nixon’s “war on drugs,” in reality, meant a war on poor people in a scenario where the U.S. funded the Iran contra rebels through selling drugs in black communities. Even though community members support the system through their taxes and in other ways, war is being made upon them, he asserts. These kinds of injustices are an outrage in our society, and hearing these stories, I feel it too.

The positive side, if there is one, is that the events of Ferguson generated a kind of energy that had not been seen before; where people were willing to stand up and face down police with guns and tanks on American city streets. In that moment, people who were fed up became connected to others who were fed up, and something remarkable was put into play. Ragland shares stories from many others who have been standing up for decades, and of those who stepped out of their own marginalization and made their voices heard.

For his part, Ragland hopes The Truth Telling Project can help raise consciousness in our culture. Already some groups with this focus, like A Conscious Conversation St Louis [9], have been born out of The Truth Telling Project, which is reaching out to communities and sharing what has been done via a “toolkit” that shares their story of how The Truth Telling Project started.

Research from political scientist Erica Chenoweth shows that if just 3.5% of a given society is mobilized, structures will change [10], Ragland informs me. In this moment, more people are joining together for human rights and dignity, including for Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, LGBTQ issues, and others. More people are waking up! Truly a small number of people can change society, he reiterates, bringing to mind a quote commonly attributed to cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”

In closing, Ragland points out how profoundly capitalism and materialism disrupt human lives, making us cogs in a system. Martin Luther King talked about the triple evils of materialism, militarism, and racism, rallying a crowd in 1967 with a dynamic speech about shifting from a “thing-oriented society” to a “person-oriented society.”[11] We have to begin valuing one another, Ragland insists, and that means valuing the specificity of identity as well.

We use ritual because our lives are sacred, Ragland offers. One of contemporary society’s most famous sacred books, the Bible, uses stories. If people’s lives were sacred and valuable back then enough to make the Bible into a holy text, then we are, in modern times, living out lives that are holy in days that are unholy. The initiative behind The Truth Telling Project wants to bring that sacredness back to our dignity—not just because one can boast of a good job and paying taxes—but because we are human. Our experience in and of itself is valuable, and we have move away from a focus on money and material things. We can shift; we just have to tell a better story than the one those in power are telling, Ragland asserts. We have to tell our own stories and listen with open hearts to those who have been traumatized for too long, I think. Yes: this is how we begin to shift.

Listen to the full audio interview with David Ragland here (approx. 33 mins):

Learn more about Pacifica’s conference, “Response at the Radical Edge: Depth Psychology for the 21st Century” (June 16-18, 2017)

Visit The Truth Telling Project web site at http://thetruthtellingproject.org/

[1] Learn more about the events in Ferguson at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferguson_unrest

[2] Read the full mission statement for The Truth Telling Project at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferguson_unrest

[3] See reviews for Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration and the Age of Colorblindness, at http://newjimcrow.com/praise-for-the-new-jim-crow or http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/6792458-the-new-jim-crow

[4] Transitional justice consists of judicial and non-judicial measures implemented in order to redress legacies of human rights abuses. Such measures "include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations programs, and various kinds of institutional reforms.” Learn more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transitional_justice

[5] See an interview/article about the activism of Fania and Angela Davis: http://www.yesmagazine.org/issues/life-after-oil/the-radical-work-of-healing-fania-and-angela-davis-on-a-new-kind-of-civil-rights-activism-20160218

[6] Read an article about activist Cathy Daniels (a.k.a. Momma Cat) serving dinner to protestors outside the Ferguson police department: http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-ferguson-thanksgiving-20141128-story.html

[7] Read an account of the story of Tamir Rice at https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/nov/21/tamir-rice-cleveland-police-shooting-civil-rights

[8] Learn more about discovery in the McGraw Hill Texas textbook at http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/10/23/450826208/why-calling-slaves-workers-is-more-than-an-editing-error

[9] Find out more about A Conscious Conversation St. Louis at https://www.aconsciousstl.org/

[10] See a video or transcript of Erica Chenoweth’s TEDx Boulder talk on the 3.5% at https://rationalinsurgent.com/2013/11/04/my-talk-at-tedxboulder-civil-resistance-and-the-3-5-rule/

[11] Read about MLK’s 1967 speech about materialism, and becoming a person-oriented society at https://www.democracynow.org/2013/1/21/dr_martin_luther_king_in_1967

David Ragland, Ph.D., is the Co-Founder and Co-director for the Truth Telling Project of Ferguson and a visiting professor at United Nations Mandated University for Peace in Costa Rica. He researches and thinks about the moral dimensions of violence and trauma against vulnerable populations in the U.S., as well as envisioning a world with reduced violence on all levels. As an activist, educator and scholar, his recent and past work is the ground level in his home community near Ferguson, Missouri. David’s analysis is drawn from the radical teaching and scholarship of Martin Luther King, particularly in his description of the triple evils of Militarism, Racism and Materialism, as an ever-present part of American life. Calling us to a shift in values, Dr. Ragland focuses specifically on how our society conceives justice as retributive and proposes a shift toward restorative justice to transform communities and criminal justice system and take America’s turbulent history and life experiences into account for policies at all levels. Follow David and The Truth Telling Project on Twitter: @davidragland1 or @TruthTellersUSA

David Ragland, Ph.D., is the Co-Founder and Co-director for the Truth Telling Project of Ferguson and a visiting professor at United Nations Mandated University for Peace in Costa Rica. He researches and thinks about the moral dimensions of violence and trauma against vulnerable populations in the U.S., as well as envisioning a world with reduced violence on all levels. As an activist, educator and scholar, his recent and past work is the ground level in his home community near Ferguson, Missouri. David’s analysis is drawn from the radical teaching and scholarship of Martin Luther King, particularly in his description of the triple evils of Militarism, Racism and Materialism, as an ever-present part of American life. Calling us to a shift in values, Dr. Ragland focuses specifically on how our society conceives justice as retributive and proposes a shift toward restorative justice to transform communities and criminal justice system and take America’s turbulent history and life experiences into account for policies at all levels. Follow David and The Truth Telling Project on Twitter: @davidragland1 or @TruthTellersUSA

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.

Bonnie Bright, Ph.D., is a graduate of Pacifica’s Depth Psychology program, and the founder of Depth Psychology Alliance, a free online community for everyone interested in depth psychologies. She also founded DepthList.com, a free-to-search database of Jungian and depth psychology-oriented practitioners, and she is the creator and executive editor of Depth Insights, a semi-annual scholarly journal. Bonnie regularly produces audio and video interviews on depth psychological topics. She has completed 2-year certifications in Archetypal Pattern Analysis via the Assisi Institute and in Technologies of the Sacred with West African elder Malidoma Somé, and she has trained extensively in Holotropic Breathwork™ and the Enneagram.